His name is Fibblestax. It’s him we have to thank for words like mother, whisper, crackers and rain.

You probably thought these elemental English words had no single inventor. I certainly did. But author Devin Scillian reveals the truth about where names really come from in his delightful children’s book, Fibblestax.

I was first introduced to Fibblestax through Hugh Levaux, a client for whom I named the clinical trial research company, Bracket. In our second meeting, Hugh told me what he recently told his five-year-old daughter, “You know who I met today? Fibblestax.”

I looked at Hugh quizzically, quickly blinking the way one does when confused or lost in conversation.

“Uh...who’s Fibblestax?” I asked.

Hugh was stunned. “You don’t know Fibblestax?! He’s the boy who names everything!”

|

| Go ooooon! |

After our meeting, I ran home (on BART) and found Fibblestax on Amazon. With an inkling that this book about the boy who named everything would be important to me, I sought and bought a first edition signed by the author, Devin Scillian. (At the time, I thought that I’d like to talk with the author someday. Months later I did, and our conversation will be featured in a future blog post.)

Like Navin Johnson when the new phonebook arrived, I greeted the delivery of Fibblestax at my door with loud outbursts of joy.

Fibblestax is here! Fibblestax is here!

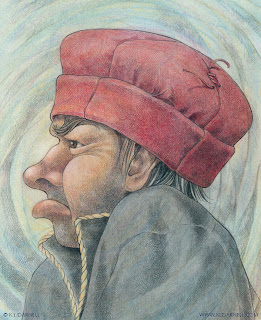

Fibblestax is beautifully illustrated by calligrapher Kathryn Darnell. Adorning the covers and every page between, her rustic pencil illustrations are richly textured. The endpaper features a selection of words writ large and small in varying styles of calligraphy. They are words for which we have Fibblestax to thank: daffodil, armadillo, hatchet, rutabaga, jug.

|

| Kathryn Darnell illustrates why calligraphy means beautiful writing. |

His name was Carr, a red-faced man

who sat on a hickory trunk,

And gave terrible names to wonderful things

like toad and snake and skunk.

He thought up all the awful words

in a careless, haughty way,Words like sphere and xylophone

and others I can’t say.

Carr, with a face befitting his names. Fibblestax spent his time considering the names Carr invented and dreaming up better ones. Fibblestax was named by Carr, so it’s understandable he would want to outsmart the one responsible for his own awkward moniker.

Fibblestax: A boy and his names.

Fibblestax taunted Carr ever-sweetly with names better than the ones Carr dredged up:

This gloobywickus in my cupTaking offense, Carr challenged Fibblestax to a naming contest. An announcement was issued to the community:

why it looks like cream.…

And I much prefer the sound of flowers

to the sound of gunnywunks.

The things we say,

the trinkets of our tongue.

Shall it be Carr the elder

or Fibblestax the young?By order of the mayor,In this epic naming battle for the ages, the mayor would describe a thing that needed a name, and Fibblestax and Carr would each name it, then the people would judge. Fibblestax happened to come up with the very words we use today for those things. In all fairness, the deck was stacked against Carr. [Hey, Devin, how about a sequel from the perspective of Carr, a la Grendel?]

come this very day

and weigh these worthy wordsmiths

come without delay.

As a namer, I appreciated the inventiveness of Carr’s ugly words. Quoting Mr. Scillian from our soon-to-be-published interview, “The words had to be wrong in just the right way.”

Fibblestax vs. Carr: War of the Words

Consider for yourself the names invented by each: Carr came up with droog, where Fibblestax came up with rain. And Carr called poonies what the boy called crackers (“for that’s how crackers sound”).

The last word Carr could not name, for it described a feeling Carr never felt:

This is that feeling, that very strange feeling,Fibblestax knew what to call that feeling. He called it love.

a dreamy kind of cheer.

That feeling that makes you feel so good

when a special friend is near.

The judges swooned. Fibblestax was victorious. At the celebration, there was lots of hugging and crying and singing into the night. I’d wager Fibblestax invented the word kumbaya at some point.

The story closes with a conversation between the author and Fibblestax, suggesting the boy give himself a better name:

This is love.

“Oh no,” he says, “I’ll not do that.The book about the boy who names everything admits to the limits of names. It’s true, names can’t do everything. A great product can succeed despite a lousy name, and a great name won’t salvage a lousy product.

It’s a little reminder for me

To always find the perfect name

for all the things I see.

And yet,” he says, “it’s what’s inside.

A name sometimes distracts.

For everyone’s a special soul.

Even one named Fibblestax.”

But names are not nothing, either. They do matter. Every time you think of a thing, you think of its name. Every time you talk about a thing, you speak its name. I, for one, would much rather have wonderful words echoing in my thoughts and speech instead of ugly ones. Wouldn’t you?

Thank you, Devin, for introducing us to the quintessential namer, Fibblestax. And thank you, Fibblestax, for your wonderful names.

Readers, stay tuned. My interview with author Devin Scillian will be posted soon!